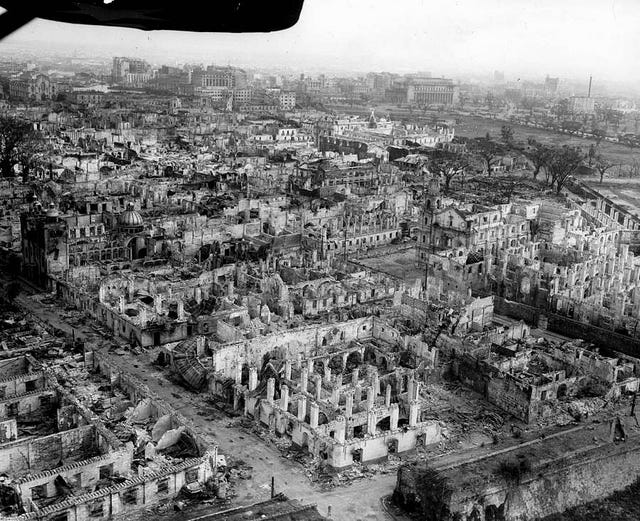

It's March, 1945 in the Philippines, 6 months before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought a conclusive end to World War II.

The destruction of the Battle of Manila was unimaginable. As the Japanese army tightened its grip on the capital to withstand artillery from American & Filipino forces, entire buildings and city blocks were razed to the ground. Among Allied cities, only Warsaw suffered more. When the fighting subsided, 100,000 civilian lives were lost.

Joseph McMicking survived the Battle of Manila. Serving in General Douglas MacArthur's Army as a Captain, the Stanford-educated, Philippines-born officer of Scottish and Spanish descent, was a man of the East and West.

Seeing the Manila streets where he grew up disintegrated to ashes must have been a horrific sight. But life had other plans for Joe, or rather - he had other plans for life.

Among The First VCs

In 1948, Joe and his brother founded McMicking & Co. in San Francisco.

The firm invested in Ampex Corporation, which made tape and video recorders from captured German technology. Ampex made history as one of the first IPOs from Silicon Valley (when the term didn't exist yet!), listing in 1958 after Hewlett Packard in 1957.

From Steve Blank's The Secret History of Silicon Valley:

Ampex business took off when [Fred] Terman introduced Ampex founder Alex Poniatoff to Joseph and Henry McMicking. The McMicking’s bought 50% of Ampex for $365,000 (some liken this to the first VC investment in the valley.) McMicking and Terman introduced Ampex to the National Security Agency, and Ampex sales boomed when their audio and video recorders became the standard for Electronic Intelligence and telemetry signal collection recorders.

What most people in Silicon Valley today don't know is that this early venture capitalist was simultaneously working on what we now call a side hustle.

Joseph McMicking is building a city from scratch.

Makati: a 1950s Startup City

In 1931, Joe married a childhood friend - Mercedes Zobel de Ayala, a scion of the Filipino conglomerate Ayala y Cia.

Founded in 1834, Ayala by then had over 100+ years of experience bringing the Industrial Revolution to the Philippines. It started with distilleries and expanded over the decades to utilities, transportation, banking, and insurance.

After serving in the war, Joe returned to help his father-in-law revive the now struggling Ayala. Mercedes and her two brothers inherited 1650 hectares of swamp and farm land in the sleepy town south of Manila called Makati.

By 1948, Joe had the early versions of a master plan to transform an area roughly the size of midtown Manhattan into the new business and financial capital for the Philippines.

This was harder than it seemed. World War II ruined the economy. William Manchester, Gen. MacArthur's biographer, quantifies the destruction:

"Seventy percent of the utilities, 75 percent of the factories, 80 percent of the southern residential district, and 100 percent of the business district was razed."

Though the McMicking and Zobel de Ayala families used to live in the heart of Manila before the war, Joe found a better strategy in founding a new city from scratch, rather than rebuild Manila to its former early 20th century glory. And it worked.

City as a Product

The plan started with residential "villages" - essentially gated communities for the elite fleeing the ruins of Manila. As houses were built, commercial establishments sprouted. By the late 50s, Makati started resembling the typical American suburb.

Throughout the 60s, Ayala y Cia evolved into the Ayala Corporation. Ayala consolidated its holdings in real estate and banking, while entering the nascent food manufacturing, semiconductor, and telecommunication industries. As Makati's business elite expanded their businesses through the 60s, a financial district started taking shape along Ayala Avenue.

The Ayala Corporation keeping a tight rein on urban planning - by controlling the supply of commercial and residential land to keep prices rising, limiting air rights, controlling land use, granting land to religious orders to operate schools, even building a private security force.

Throughout the economic crises that rocked global currency, sugar, and oil markets in the 1970s, Makati continued to grow as the country's central business district, with its highly educated workers forming the backbone of the country's emerging middle class.

Joe wisely deployed a tightly centralized strategy to build Makati. The flywheel was simple. First, seed crowdchoice by selling the vision of a modern urban city. Inspired by Daniel Burnham's work, this urban development plan focused on seeding the city with wealthy business families who wanted to build homes on newly developed parcels of land, far from the destruction of Manila.

Second, get these families to invest in the commercial zones nearby. As big businesses flocked to Makati, entrepreneurs set up a thriving retail scene and nightlife to serve the growing city.

Third, growing property values unlocked even more capital from banks, which led to more businesses and even more residents.

Meanwhile, the decades-long economic boom funded a prosperous city government, where social services like public education, basic healthcare, and even burial benefits for senior citizens are provided for free to the city's ~500,000 residents. Measured by the size of its balance sheet, Makati is the richest city in the Philippines, with assets greater than the next 4 cities combined.

Cracks Show

Fast forward to 2021, and the economy is once again devastated, this time not by invincible machines of war, but by invisible microbes.

The Philippines is the worst hit economy in Southeast Asia, with GDP shrinking by almost 10% in 2020. It's a major setback in alleviating poverty because emerging markets need to growth 7-8% just to keep up. 4.2 million are unemployed.

The good news is that Filipinos are rebuilding from the ground up. Business registrations logged by the Trade and Commerce Department hit ~430,000 in Q1, on top of the 900,000 registrations in 2020.

But unlike the 50s, it's highly likely that the recovery will be driven outside of Makati because the vast majority of entrepreneurs are priced out.

Joe built a city with the technology of this time - centralized urban planning, conglomerate economics, control of land, and a young capital market. While this worked in the post-World War II era, centralized development started showing cracks in the 2000s, namely in housing, free and open markets, and education.

Problem 1:Affordable Housing. Makati has ~500,000 residents but a daytime population of 1 million, driven by people who work there but live outside the city. In Makati, NIMBYism has root access via incredibly tight deeds of restrictions that prevent land owners from building higher density housing.

From the 60s to the 80s, currency depreciation and government expropriation of private businesses raised an entire generation reliant on real property to build wealth. Makati’s residents will protect those gains at all costs. This dynamic is clearly seen in the distribution of property prices all throughout Metro Manila, with Makati as the red zone in the center:

Send a drone 100 meters up, and you'll clearly see the housing inequality: skyscrapers surrounding by a sea of urban slums.

But it's not because of lack of land. Pan to the left and get a wider shot of that same photo above, and this is what you'll see.

That huge strip of green in the lower left are the private gated communities of Dasmariñas Village and Forbes Park. There is more land allocated to these private enclaves where low-density housing dominate, versus the entire commercial district of the city. But because of a captive city government, building cheaper higher density housing near the central business district is close to impossible.

If these enclaves seeded the city in the past, they are now ceilings to its future.

Problem 2: Free and open markets. This isn't unique to Makati in itself, as the Philippines as a whole ranks in the bottom half in the World Bank's Ease-of-Doing-Business survey, which ranks countries on indicators such as starting a business, registering property, accessing credit, trade across borders and so on. But this massive market is kept relatively closed by an entrenched oligarchy - mostly headquarted in Makati - that seeks to keep its hold of the local economy by minimizing foreign competition.

As a result, though the Philippines has a larger population than Thailand, Malaysia, or Vietnam, it has significantly lower levels of foreign investment:

Problem 3: Education. Despite its proximity to big business, Makati never really gave birth to a globally recognized science and research university. This is like Boston without MIT, New York without Columbia, and the Bay Area without Stanford. Some schools tried. For example, the high school I went to tried to expand its campus to support university courses in the 80s and 90s, but was immediately blocked by local NIMBYsm.

What Happened? A Tale of Two Platforms

The overarching problem is centralization. Joe was limited to the tools of his time to jumpstart an economy. Like the technology platforms of today, Makati the city was eventually captured by a ruling elite, accruing power that rivals even the state.

The same dilemmas for sharing power, rights, and economic privileges that Apple, Google, and Facebook face have played out slowly over decades in McMicking's startup city, precisely because it is so hard to distinguish where a product ends and platform begins.

The Means of Creation newsletter describes this dilemma well, using Apple and iOS to illustrate:

Apple is a product company. They famously obsess over details, and want every element of the user experience to be perfect. They require total control, because it allows them to use their taste to make choices that are frustrating at first for users (like removing the headphone jack) but then turn out later to be prescient and perhaps even courageous. There’s no question, they make the best products, and they extract a steep price for them.

But iOS is a platform. And the habits you acquire by being a good product company do not always help to run a platform effectively. Too much control, taste, and value extraction can break a platform. These three principles served iOS well in the early days when the platform was nascent and needed to be hand-nurtured. But now that the iPhone is ubiquitous, the App Store has become part of the basic infrastructure of the internet. And many of its policies around in-app purchases and tightly controlled App Store curation are not well-suited—and in fact harm—the broader ecosystem.

Ayala is a product company. But Makati is a platform. And if Apple has a hard time making this distinction, so too can the people behind a vast conglomerate with decades-old interests in banking, real estate, utilities, energy, healthcare, and telecommunications. Though the C-suite leaders of Ayala are incredibly well-liked for their humility, simple lifestyle, and commitment to nation building; a slow-moving class of middle managers resistant to change has sprouted like weeds. The head of international sales was once quoted, without a hint of irony, something that would titillate a rightwing Republican's wildest dreams (emphasis mine):

The fact that there is nobody in the Philippines who regulates urban planning has been great for Ayala Land, because we are probably the only company there that has the scale financially to take on large plots of land.... By developing big tracts of land, we become the government; we control and manage everything. We are the mayors and the governors of the communities that we develop and we do not relinquish this responsibility to the government.... But because we develop all the roads, water and sewer systems, and provide infrastructure for power, we manage security, we do garbage collection, we paint every pedestrian crossing and change every light bulb in the streets – the effect of that is how property prices have moved.

So how do these problems get solved? In general, I think we have two directions:

Solve these problems inside Makati

Solve these problems outside of Makati

One can certainly imagine DeFi solutions for the first, such as equity tokens that can fractionalize ownership and governance of Makati's gated communities to enable higher density housing, or a Diem-like currency instrument redeemable across its businesses. But let's give Ayala's managers a chance to figure this out themselves.

Instead, I think the 2020s will see a critical mass of Filipinos opting for the 2nd strategy because a new generation of entrepreneurs will realize the limits of conglomerate-led central planning and thus experiment with more decentralized solutions.

This is a soft exit, with users voting with their feet to move domestically, rather than join the 10 million+ Filipinos working overseas.

We now see clear trends of this happening. On the 'supply-side', a nexus of cloud, crypto, and communications technologies have now made this exit possible. On the 'demand-side', the timing is right, for the following reasons:

Filipinos are solving pandemic problems with decentralized solutions. The state's pandemic response has made "national vs local" a more salient mental model in the minds of Filipinos. Vaccine procurement and distribution has been led by local city mayors. Over 6,700 "community pantries" - food banks with donated essentials staffed by volunteers - have sprouted in a few weeks, after a single food bank went viral and was replicated by countless others.

Economic catastrophe has sparked a Cambrian explosion of new businesses. As mentioned earlier, Filipinos are rebuilding from the ground up. Business registrations logged by the Trade and Commerce Department hit ~430,000 in Q1, on top of the 900,000 registrations in 2020. These are impressive numbers in such a short period of time for a population of 110 million.

Capital is hungry to be deployed. Central bank data shows that total deposits increased 9% year-on-year to PHP ~15 trillion ($312 billion), but total loans stayed flat at PHP ~10 trillion ($205 billion), leaving more than $100 billion in domestic capital waiting to be allocated. As overseas Filipinos come home to retire, they bring their wealth to their hometowns. It's now not surprising to drive to remote farmlands but see clusters of housing and small shops bootstrapped by remittance dollars.

"Next Wave Cities" are driving growth. Limited usable land and expensive prices are giving rise to over 20 next wave cities, who will now compete with Makati to attract new residents and businesses.

Greater awareness of geopolitics. As a wave of illegal Chinese migration to the Philippines in 2018-2019 happened, many locals got priced out of the property markets. And as islands are reclaimed by the PLA in the South China Sea, more and more Filipinos are realizing that they need to build new cities on their own, or else China will.

How will these new cities be bootstrapped?

At this point, we're nearing the realm of the speculative. But if the trends above hold through the 2020s, I foresee 3 rough models, all rooted in existing legislation and urban developments.

From a scale of large to smaller communities:

Cloud towns: the Philippines already has a regulatory framework for special economic zones that grant incentives to exporters. Traditionally, these have been large companies. But with community bargaining + equity-like tokens, it's not impossible to imagine collectives formed among the 2 million people working as freelancers. Members can start by collectively bargaining for legal protection, then evolve to acquire and develop property together, and fund public goods such as schools. (This isn't entirely new - the Philippines already has a party list system, where by sectors such as laborers and overseas workers are represented in Congress). With crypocurrencies, these towns will bypass national restrictions that prevent foreign education providers to serve local students.

Cloud villages: This is a smaller version of towns, often just composed of a few blocks. One example is "Sinigang Valley" in the Poblacion area of Makati. Here, a small group of startups decide to co-locate their offices and open residential units for their employees. More startups mean more demand for local retail businesses and for legal, accounting, and health services, which in turn attracts more startups. Cloud villages also help solve a perennial problem faced by many businesses: a stable internet connection. By banding together, startups can better demand better services from telco providers.

Cloud islands: this is digital nomadism taken to the island frontier. The Philippines has more than 7,000+ islands, and less than half have permanent human settlements. As satellite internet becomes a reality, expect more remote outposts of knowledge workers plugged into the global economy, but working in paradise. Projects such as TAO have been long treasured secrets.

The Island Chain

At the end of the day, it's still incredibly inspiring to learn how Joseph McMicking built both a city and a tech company in two different hemispheres. But now we have the tools to scale his dream and share prosperity more widely by building more Makati's.

Decentralization is deeply rooted in Filipino culture and history. This is the post-colonial end state that brings the archipelago full circle with its historical roots. After all, before the Spanish conquests in the 1500s, there was no such thing as a Philippine nation state, just a collection of islands entrepôts sustained by rich trading networks with China, Java, Sumatra, and Borneo, and as far out as India and the Middle East. Maybe this isn't the beginning of a new history, but simply a return to it.

Very interesting article -- I had never heard of Makati.

One explanation for some of the recent issues you describe is subdivision itself. The big mistake the developers made was relying on freehold (with deep restrictions) rather than leases. Freehold ossifies the urban fabric. Rarely are restrictions or rules *removed* so over time risk-averse NIMBYs worried about their property values put city governments in a stranglehold.

It seems as though NIMBY is the logical end of subdivision, especially if you go the single-family-house suburban route.

There's really nothing "right-wing" about the Ayala person's statement. Having a single company with a concentrated interest in the whole would almost certainly invite a more dynamic urbanism, as long as that company doesn't sell off all the property in perpetuity with restrictive deeds. They're arguing for a residual claimant on the value of the city. That's neither left nor right. It's just good economics.